Perfect Form: Computer Vision for Powerlifting

Computer Vision ProgrammingAt this point in my career, I have gained the confidence in my machine learning research and engineering abilities that I knew that I could solve hard problems and add real value to companies. However, I had a concerning revelation: I was entirely dependent on someone else managing the deployment and infrastructure. I had helped build a neural network factory with Agentic AI. The entire system ran on dedicated Kubernetes clusters across different environments on GCP. While I was able to make important contributions to this system, I was only able to translate my ideas into features and bug fixes because the deployment had been abstracted away from me. Perhaps people working at sufficiently large companies can decide to skip learning anything about deploying models and instead hand off their results to a separate team. But if I wanted to have a high impact in a startup environment or ever meaningfully build something independently, it was clear to me that this was a shortcoming that I needed to resolve.

Learning Deployment Theory

As a first step, I carefully read Deep Learning in Production. I believe I was the target demographic for the book: I had ample experience training deep neural networks and a reasonable software engineering foundation, but I did not know much about deploying models. Additionally, I was comfortable using the book more of a map capable of pointing me in the right direction than a compendium of best practices. Would I master Kubernetes from reading this book? Not even close. But I would get exposed to the high-level ideas and start to identify the types of problems that make it a good tool to select. There is no shortage of more in-depth tutorials and documentation for Kubernetes or any other mature tool that I could review as needed.

I really enjoy reading technical books, and I believe they can be great resources. But in general, I find reading them to be relatively low-yield. This is true whether I think about the dreaded Jackson or a simple engineering book in this case. Detailed reading is necessary but not sufficient for understanding the subject matter. Until I have worked through the code and tried to implement the ideas outside of the sample project, I have not properly internalized the ideas of the book. Therefore, I knew that if I truly valued learning about model deployments, I would need to create a fresh project from scratch that would allow me to apply the principles in the book, debug the code, and experience first-hand the technical tradeoffs of different approaches.

Now I had a (path towards a) solution in search of a problem. I probably could have just modified the sample problem in the book or implemented a simple architecture using any of the canonical toy datasets (CIFAR-10, MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, Iris, etc.). However, I knew that this class of problem was too uninteresting for me to take seriously and properly explore the principles of the book. Rather, I needed a problem that I would actually be passionate to solve and would spend the late nights after work debugging when components would inevitably fail. As I thought about my hobbies and where I could usefully inject deep learning, I quickly landed on powerlifting as the domain for my specific problem.

Computer Vision for Powerlifting

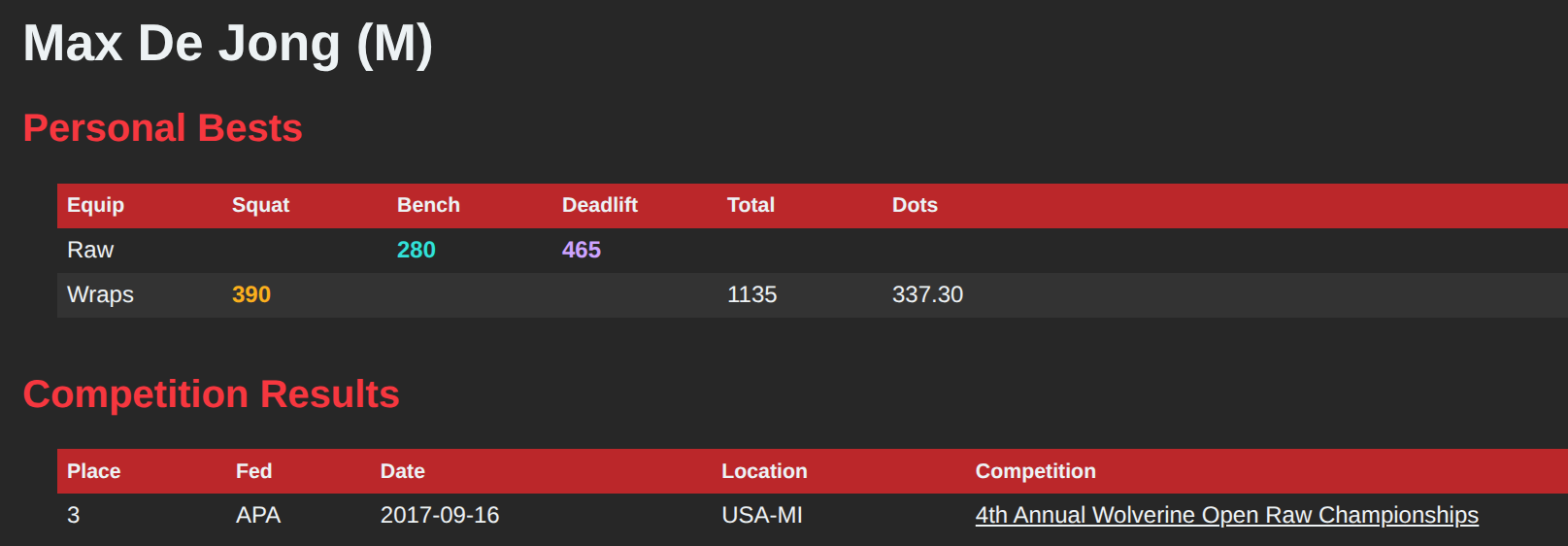

As a brief aside, I started strength training back in 2014. Although I started at the absolute bottom, with minimal prior exposure to lifting or muscle mass, I fairly diligently continued my training since then with minimal non-Covid breaks. As a result of compounding these efforts, I achieved a somewhat respectable powerlifting total (roughly 1300 pounds/375 Wilks). This will (rightfully) not impress any high level powerlifters, but I did acquire enough domain knowledge through years of training to see the opportunity for combining the latest computer vision models to assist me in my training. I decided that I would identify a collection of models that I would learn how to deploy to solidify my understanding of the ideas in the book and form a project that would keep my interest.

My last powerlifting competition before Covid, courtesy of Open Powerlifting.

My last powerlifting competition before Covid, courtesy of Open Powerlifting.

Eventually, I landed on the specific subset of computer vision models focused on human 3D pose estimation. I was curious to understand the quality of extracted 3D coordinates from videos I could record on my phone from state-of-the-art models. This is a long-standing research problem, which means that many open source models and weights are available under public repositories. I quickly got adept at cloning a new repository, creating a new Docker container to avoid contaminating my local CUDA environment, and setting up a virtual environment to evaluate the different off-the-shelf solutions. Unfortunately, I did not find an existing solution that satisfactorily estimated the 3D position of the keypoints that would be required to assess lifting form across the three main powerlifting movements: squat, bench, and deadlift. In particular, many of the models struggled with occlusions and temporal consistency across frames.

However, there were some redeemable aspects of many of the different models that I did try. In general, I saw the greatest results using top-down approaches. In this architecture, the bounding boxes of people are first detected in each image, then the keypoints in image coordinates are extracted, and finally these keypoints are transformed into 3D world coordinates. This separation of responsibilities naturally leads to three specialized deep learning models, each trained for a specific task, rather than a single model trained end-to-end. In most of the academic repositories that I found, the coupling between these different models was quite tight: the code was written to work with a specific model architecture and version with no thought given to decoupling the models to facilitate modularity or flexibility. This presented a natural opportunity to me; if I could decouple the individual models associated with the top-down approach, I could upgrade individual models as needed in hopes of arriving at an end-to-end system capable of performing at the level required to be useful for my specific application. Suddenly, I had a modular framework where I could plug in different combinations of models and tweaks to optimize performance.

Architecting a Solution

At this point, even my least astute reader will notice the obvious scope creep. I went from reading about deploying a single model behind an endpoint to a attempting to build and dpeloy a full machine learning system comprised of many models that had to correctly communicate across agreed upon APIs and response payloads. In this case, however, I don’t think scope creep is bad. Yes, the project became a much larger endeavor than necessary if my only goal was to validate my understanding of the book. I would argue that the real issue is that this goal would not have been sufficiently audacious. Solving a harder problem that would capture my interest and force me to learn more deeply about the engineering involved with serving trained models seemed worth the additional effort required.

Perhaps foolishly, I boldly pressed onward. I did not work fast, and I did not work efficiently. But I kept making progress iteratively, taking the time to step back and pick up new skills along the way. I ended up learning so many useful skills I had not needed yet. I will not claim to be an expert in any of these areas, but I gained several new abilities:

- Designing effective API contracts.

- Creating good patterns for microservices.

- Writing efficient Docker containers and combining CUDA with Docker.

- Optimizing Docker image sizes to minimize cold boots.

- Orchestrating services with Docker Compose and later Kubernetes.

- Learning distributed REST APIs and networking.

- Designing effective databases and performing schema migrations.

- Transcoding and re-encoding videos across file formats.

I could likely add another dozen items to this list, and I could easily exceed my readers’ appetites with writing way too much about any one of them. Out of respect for your time, I will spare you a detailed write-up on these admittedly elementary topics. But a fair summary is that I gained exposure to many new tools and frameworks that I had previously not used in my career. And while I had not required experience with these in my previous roles, I was able to use many of these skills to suddenly become a valuable resource on a team that skewed towards scientists rather than engineers, which allowed me the opportunity to go deeper in many of these areas and compound my initial learning.

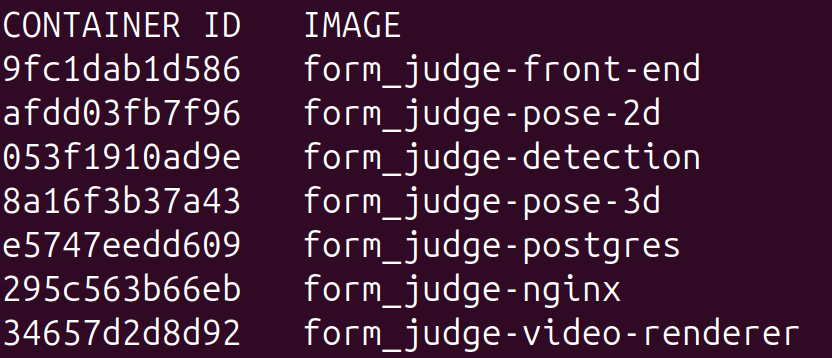

In general, I would typically tackle a single microservice at a time. Eventually, the number of required microservices grew to the point where learning Docker Compose quickly returned a handsome return on the invested time. As the project matured, it eventually grew into 7 different microservices, each with a specific responsbility:

- Computer vision model #1 - object detection

- Computer vision model #2 - 2D pose estimation

- Computer vision model #3 - 3D pose estimation

- Postgres

- Video renderer

- NGINX reverse proxy

- Simple front end written in Dash

All of the containers created for analyzing powerlifting form.

All of the containers created for analyzing powerlifting form.

At the end of the project, I took the final step and migrated to Kubernetes for orchestration. This was certainly overkill for this project, but I gained exposure and experience to a complex tool that had previously been a scary black box filled with unintuitive abstractions whenever I came across it at work.

Final Product (For Now)

So far, I have focused on the translatable skills that I gained during working on this project. More interesting, however, is looking at what I actually built as a result of all of this effort. A demo of the full tool is shown below, where a video is uploaded, processed by all of the backend microservices, and then a final page showing the video and accompanying analytics is displayed. The clip for this demo video was not chosen because it makes the tool look impressive but rather because it nicely illustrates the challenges of using computer vision models for this application: the occlusion of joints and lack of temporal consistency result in obvious artifacts in the video.

To further break down what is happening between each of the computer vision models, I also added a set of debug endpoints that allow us to visualize the intermediate artifacts that are produced. While I left the previous video completely raw to illustrate the required processing time, I edited this video to skip the inference steps, since the previous video already provides a sense of the user latency. In this video, we can clearly see the object detection identifying the lifter in each frame, then the 2D pose in image coordinates overlayed onto the image, and then finally a projection of the 3D geometry of the pose.