Perfect Form: To the Cloud

Computer Vision Programming Cloud DevelopmentI previously created a backend and frontend that combined the latest computer vision models into a local application that allowed me to analyze my powerlifting form from standard video recordings. I used this application to analyze several lifting videos for myself as well as a few friends. One of these friends innoculously asked me one night, “What have you learned about your form through your fancy application?” I had to sheepishly admit that I did not really have any actionable takeaways as a result of analyzing my training videos using my application.

There were certainly open questions around the quality of the extracted biomechanical metrics relative to the precision required to have a useful training tool. Truthfully, though, the bigger hurdle was simply how cumbersome the application was to use. Even as the creator, I did not want to boot up my desktop computer, spin up all of the pods, and then wait for all of the model inference to complete. While my friends were supportive of the project and curious about the technology, they also needed a better interaction pattern than emailing me videos, which I would analyze locally before emailing them back results.

The starting point from the last iteration. Note the local URL. Yes, I shamelessly developed the UI for my vertical monitor.

The starting point from the last iteration. Note the local URL. Yes, I shamelessly developed the UI for my vertical monitor.

Improving the Prototype

I believed that there was value in what I had built. Or at least that I could make it valuable to the narrow audience of analytics-minded strength training enthusiasts with additional effort. It was clear to me that two improvements would be required:

- Improve prediction accuracy 3D keypoint position and resulting biomechanical metrics to reliably extract actionable insights from videos.

- Migrate the application off my local computer and into the cloud.

If I could complete both of these items, I would have an easy, self-service tool that my friends and I could use with minimal friction. And if I could complete them well, I might even have a SaaS product that could inform the training of other users.

However, neither of these steps was particularly simple, each for a different reason. Improving end-to-end performance of my 3D pose estimation pipeline was non-trivial because I believed that I had already pushed the open source models as far as they could go (or at least up to the Pareto Principle of performance), and there was not a clear direction of further improving performance. Given my background, though, this was actually the easier step in my mind. The harder step to me would be to recreate the Kubernetes service running on my local computer in the cloud. Quite frankly, this would be challenging to me in particular because I did not know much about cloud development. I decided that this was a problem that I would worry about solving only if I was able to increase the quality of the extracted biomechanical metrics outputted from the platform.

So that is what I set out to do. As expected, I did not make much progress in improving the outputted metrics by gluing together new open source models in different configurations. The off-the-shelf models performed well in their respective arenas on the appropriate general evaluation problems. Yet the specific qualities required for lifting form analysis were lacking. Specific examples of these shortcomings include occlusions, particularly the unavoidable type where a limb is not visible due to the lifter’s body or the post of a squat rack, and physics-breaking pose estimates that varied significantly from frame-to-frame despite smooth transformations of the lifter’s body. Targeted changes to the models to improve the robustness to occlusion and enforce tighter temporal consistency across frames produced promising improvements, and fine-tuning these models on datasets more representative of the specific poses and videos relevant to our problem further improved the performance. I eventually reached a point where I thought the metrics returned by the service were high enough in fidelity to be broadly useful.

In addition to optimizing performance, there were a number of different challenges that only became apparent as my early users tested the platform. One example here is a friend who works out in a crowded university gym, which highlighted the need for robust subject tracking. This was always an issue but never surfaced in any of the videos that I recorded working out by myself in my garage. Adding a simple layer of subject persistence ensured that the inferred biomechanical quantities were extracted from the correct person.

To the Cloud

The second part should actually be easy if I had a containerized solution already running in Kubernetes, right? The whole point of containers and their associated orchestration is that identical runtime environments would be created across different machines and hardware configurations. There is no reason that this would not have been the case for Kubernetes deployment. But the unit economics made this approach irrelevant.

The first issue came from GPU access. When I powered on my local computer, I could use the GPU as much as I wanted. I paid a large upfront cost for my GPU, but afterwards I only had to pay for electricity usage. This means that my local Kubernetes deployment could always have a GPU assigned to the relevant pods. In the cloud, though, renting a single p2.xlarge instance would cost about \$1/hour, and the associated K80 would be far behind my RTX 3090 in both VRAM and FP32 performance due to the huge difference in the architecture age between the chips. Certainly, I would not have the luxury of having a GPU always idling, ready for the very infrequent request to hit my cluster. There is a possible solution here, which would be to implement rules to achieve scale to zero at the cost of significant complexity. Even under this hypothetical state, however, we have a second issue: the control plane would always be active. I could not justify spending \$50/month on a control plane for a cluster that might process a dozen requests.

Therefore, I needed a new approach. I had to rearchitect my system to run in the cloud without relying on Kubernetes. I had always been interested in learning more about cloud engineering, anyway, so this was a good excuse to set aside some time to learn new skills.

Learning AWS

At this point, I decided that I was more interested in learning about cloud engineering than shipping a product. If my goal was to become a solo entrepreneur, I probably could have gotten a version of my backend working relatively quickly using a combination of blindly following AI suggestions and using one of the newer, simplified frontend and backend frameworks. Supabase and Vercel, for example, both seem to be gaining in popularity by targeting vibe coders more interested in collecting Stripe payments than debugging IAM permissions issues. However, I believed that learning cloud engineering would be time well spent, since I would likely be writing code and designing systems running in the cloud for the rest of my career. Much like the initial endeavor to learn model deployment through the genesis of this project, I used this next checkpoint in the project’s evolving lifecycle as an opportunity to more deeply learn a critical component of modern technology development.

Much as with model development, I decided that I would first learn the theory of cloud development, and then augment my new understanding with a specific problem and goal. I was comfortable pausing further development on my application to gain a firm foundation into understanding one of the modern clouds. Now, which cloud was the best for me to learn? In my mind, this had a fairly straightforward answer. The startup where I work is built on AWS, so any cloud skills could be directly impactful to my day-to-day work. Additionally, AWS has the largest marketshare, making it an obvious initial cloud computing platform for someone looking to break into cloud. This decision ended up becoming a fairly substantial detour: I spent 4 or 5 months picking up cloud certifications, finding time to study in the evenings after work and on the weekends. I started with the Certified Cloud Practitioner to gain a broad understanding of the many services on the platform, built upon this understanding with Solutions Architect-Associate to actually learn how to design, build, and deploy systems to AWS, and then finished by grabbing the Machine Learning-Specialty since it was very easy and I was already in certification mode.

The product of 4 months of nights and weekends.

The product of 4 months of nights and weekends.

Rewriting Back End + Adding Proper Front End

At the end of this side quest, I had all of the theoretical knowledge required to return to running my form estimation application the cloud. I decided that I would make several major changes to the initial application I had developed locally:

- I would transition to an event-based backend. This was not necessary and would be another slowdown, but I was curious to gain experience with event-driven architectures after I felt that I had already gained basic proficiency with microservices. As an added benefit, I could easily scale resources down to zero when not in use. Since I didn’t expect to have any users most days, this was a nice feature.

- I would develop a proper front end instead of relying on the prototype I had created in Dash. This was a bit intimidating, since I had zero experience with any front end design or implementation, but it seemed non-negotiable if I actually wanted my application to be usable by someone who was not me.

In hindsight, I am glad I spent the time rewriting my entire backend from microservices to be event-driven. I think it was a valuable exercise for me, even if I lacked tangible demonstrations from the exercise. In the process I also upgraded a lot of the code to handle more general requests, since I wanted a self-serve backend that would generate reasonable values across arbitrary user inputs. As I began testing my code on videos recorded from devices other than my own phone, for instance, I was forced to first learn about the different video formats and how rotation is encoded and then second leverage FFMPEG to convert raw user videos into a common format for use with all of the downstream models. And then I rediscovered the value of FFMPEG again when I later learned about re-encoding videos for playback compatible across operating systems and devices.

There were two main migration tasks that fell outside of the normal pattern of simply translating an existing microservice into a new event-driven component. First, I knew that I needed to upgrade my local Postgres pod to a proper cloud database. While I intended to stick with AWS for as much of the infrastructure as possible, the Aurora serverless database dropped support for scaling down to zero ACUs when not in use. Initially, I migrated everything to Neon for a true serverless Postgres database. I had exclusively good experiences building on Neon and would recommend it to anyone looking for a database. However, I came to realize that the event-driven architecture would benefit greatly from using DynamoDB, which allowed for triggering both on new records and updates to the fields of existing records. So I shifted to (eventually several) NoSQL tables in DynamoDB.

GPU Access

The second migration task came back to GPUs. Evaluating the trio of computer vision models requires roughly two minutes of GPU time, so switching to CPU at the expense of even slower processing was not feasible. AWS does not offer any serverless GPU inference, surprisingly, and I did want to return to a dedicated EC2 instance that would require rolling my own custom autoscaler to avoid paying for idle GPUs. After some exploration, I landed on using Replicate, which allows for GPU inference of custom models that will automatically scale up based on usage and then scale down to zero. My experience with Replicate has been mixed; I’m grateful the company exists and offers a solution that perfectly matches my use case. However, I did not think highly of Cog, their in-house alternative to Docker for declarative container specification. It lacks the full power of Docker, which became troublesome for one of my computer vision models that relied on a custom GPU kernel that was previously built into the Docker image. I was able to set up a private python package repository to store the package requiring the custom CUDA kernel, so this was not prohibitive. Overall, though, I found that learning a new abstraction on top of Docker actually increased the complexity and developer burden.

Eventually, I created the Cog files that would be responsible for serving each of the three computer vision models required for form analysis. First was the object detection model, which I ran on a T4 on-demand for the low price of \$0.81/hour. Next, these predictions were used by the model responsible for 2D pose estimation from the video frames. Since this model required a custom GPU kernel, I chose to run it on an A40, which shared the same architecture as my local GPU, for \$3.51/hour. This model is also the most compute intensive, so using faster hardware made sense. Finally, the model responsible for uplifting the 2D pose estimation into 3D coordinates also ran on a T4. Replicate provided simple APIs for each of these models that could easily be called inside a lamba function for serverless inference within the current event-driven architecture.

Each of the computer vision models running serverless inference in Replicate.

Each of the computer vision models running serverless inference in Replicate.

Final Back End Resources

I ended up adding several features that were not present in the simple Kubernetes deployment that I had been running locally. The most noticeable of these was incorporating agentic AI into helping users arrive at reasonable interpretations and future actions rather than require them to deeply understand all of the biomechanical metrics themselves. The solution that I implemented was quite simple compared to agentic graphs that I had previously developed during my day job, but it nicely addressed the main user criticism that I had received as I started to share what I had built with friends.

After some tweaks and several checks to ensure I didn’t have any infinite event trigger sequences, I had created a robust back end with many steps, each triggered sequentially from a video upload into the appropriate S3 bucket. Once all steps were completed, the time series of the lift-specific quantities were stored in a DynamoDB table and a video containing the overlayed keypoints was persisted in S3. I later added a series of APIs using API Gateway and also integrated with Cognito for user authentication and integration. These additional requirements only became apparent as I was developing the front end, which was the next step in my journey.

Front End Development

As I had mentioned, I had zero experience writing any front end code. Yet I had a vision for a UI that allowed for some fairly complex interactions with regards to state management. Just as with many other steps in the evolution of the project, I was at a crossroads where I could pick the path of least resistance or commit to first learning the necessary skills. For the first time in the history of the project, I decided to take the path of least resistance. While I spent some time learning the basics of Next.js, the language I ultimately chose for the front end, I determined that developing front ends was not a skill that I expected to use enough in the future to warrant the time required to develop a deep understanding. Rather, I turned to Cursor and a range of LLMs to help me write the necessary code as quickly as possible. Mind you, this turned out to not be all that quick. The code base and requested features rapidly grew in complexity until the LLMs really started to struggle, and I often had to get my hands dirty to successfully commit the intended changes. After many tokens and lots of back and forth with Cursor, I was able to (co-)create a UI that I find enjoyable to use.

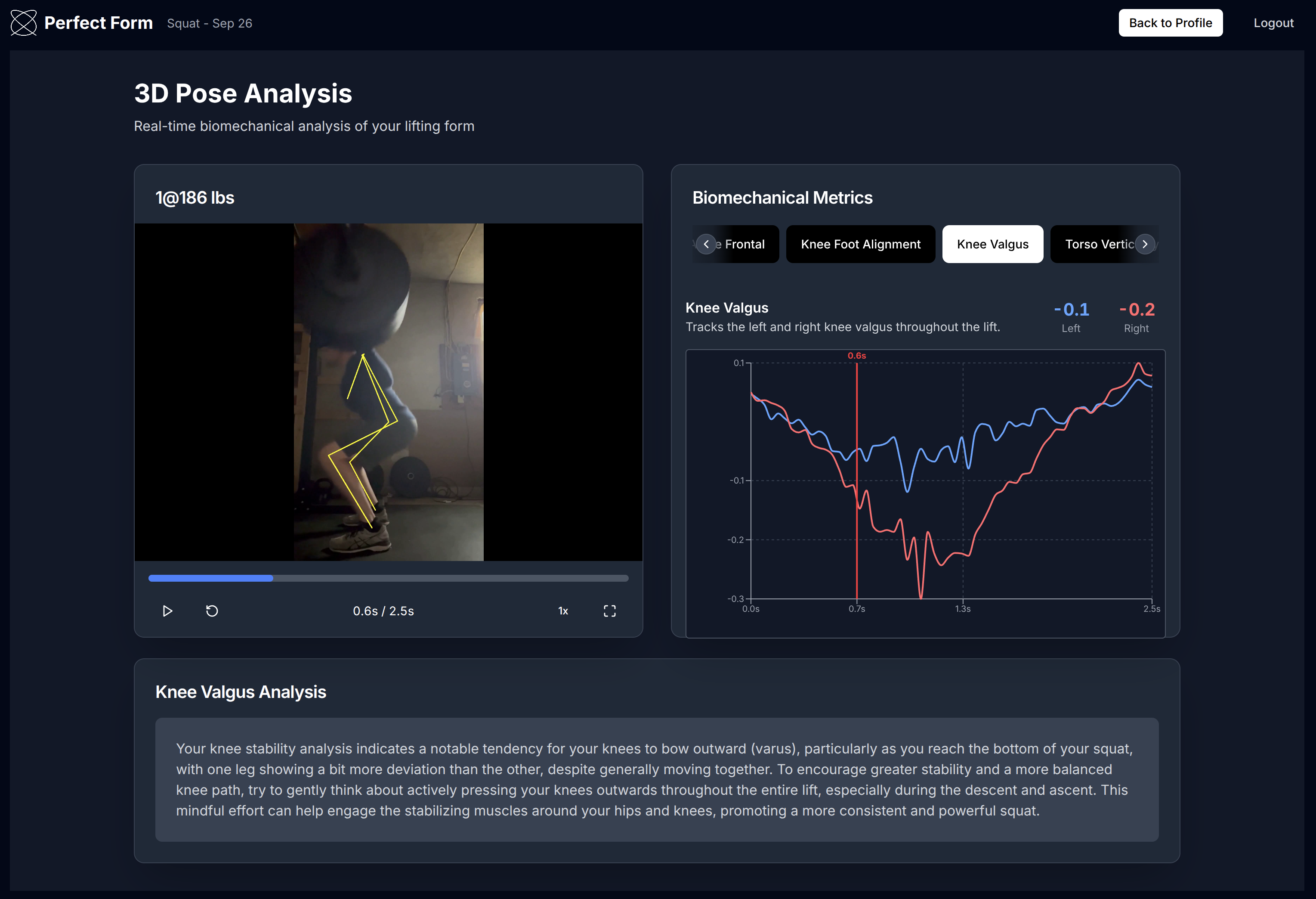

I won’t cover too much of the UI here, since the interested reader can see it in the video below. However, I will include one screenshot showing the new analysis screen to compare against the final product of the previous iteration. This version preserves the interactivity from the previous version but with an improved layout to allow the user to explore the full range of biomechanical metrics produced from the 3D pose estimation inference results. The automated analysis and suggestion text is also apparent in this screenshot.

The updated analysis screen to allow users to analyze their from through the extracted biomechanical metrics.

The updated analysis screen to allow users to analyze their from through the extracted biomechanical metrics.

(Soft) Launch

At this point, I purchased a fancy URL for my project, which came to be called Perfect Form, and deployed my front end. I had added the necessary APIs for the back end resources to communicate all of the required information to the front end, and I fully integrated Cognito for authorization on all of the endpoints. After adding some simple DDOS protection, I loaded up my Replicate account with credits and began sharing the link in a 1:1 setting with a select group of friends. I also recorded a demo video walking through the product and user experience:

I have not yet committed to actually trying to make this a successful SaaS product. If you watch the video, you’ll notice that the perspective is instructional rather than hype. I have not done any marketing about Perfect Form, and this is currently the only online reference I have even made acknowledging its existence. Curiously, there are several people who have somehow discovered the site and signed up to join the waitlist. So why would I go through this tremendous development effort to not add a Stripe link as the final step for finally receiving some compensation for the many hours invested into Perfect Form?

I wish I could offer free access to Perfect Form for interested users. Although the AWS costs associated with active users are minimal, there are non-trivial costs associated with spinning up the GPUs for model inference as well as the agentic AI LLM usage to synthesize the biomechanical metrics and score the lifting form. Simply, I am not confident that the quality of the product in its current form is something that I could feel good about charging people to use. This may change in the future, either as a result of future external developments to relevant models or renewed personal time/interest in making this a paid product that would offer a solid return on users’ money. However, if I never make a dollar from this project, it has already been a success in my eyes. I have learned so many new technologies to reach this stage, and I am proud of the platform that I built and was able to share with friends.

While I cannot offer open access to the platform, I am happy to share it with anyone interested enough in its evolution to make it this far in the post. If you are interested in trying out the platform for yourself, send me a message and I can get you some credits to explore what I built.